Sobre los cimientos de Tlatelolco, un símbolo de varias tragedias en la Ciudad de México y bajo una lluvia que cae sobre mojado estos días en los hombros de los defeños, han sonado los acordes del Requiem de Verdi en homenaje a las víctimas y rescatistas del terremoto de 1985. Un concierto de la Orquesta Filarmónica de la ciudad dirigido por el tenor español Plácido Domingo, que el 19 de septiembre de hace 30 años luchó por rescatar a sus familiares justo en ese lugar. Los cuatro murieron bajo los escombros y él lo ha recordado este viernes.

Publicaciones

Masacre de Apatzingán: Los desplazados de Castillo

Publicaciones

Esta es la tercera entrega de la reportera Laura Castellanos sobre la masacre de Apatzingán, donde se difunde cómo en la persecución contra las víctimas han participado policías estatales y municipales. Las tres entregas de la periodista registran que en los hechos del seis de enero hay una cadena de responsabilidades a todos los niveles para encubrir un cúmulo de hechos impunes que apuntan a un crimen de lesa humanidad

-> Publicado en Aristegui Noticias el 17 de agosto de 2015

Cementera Fortaleza: el monstruo gris en el Valle del Mezquital

Publicaciones

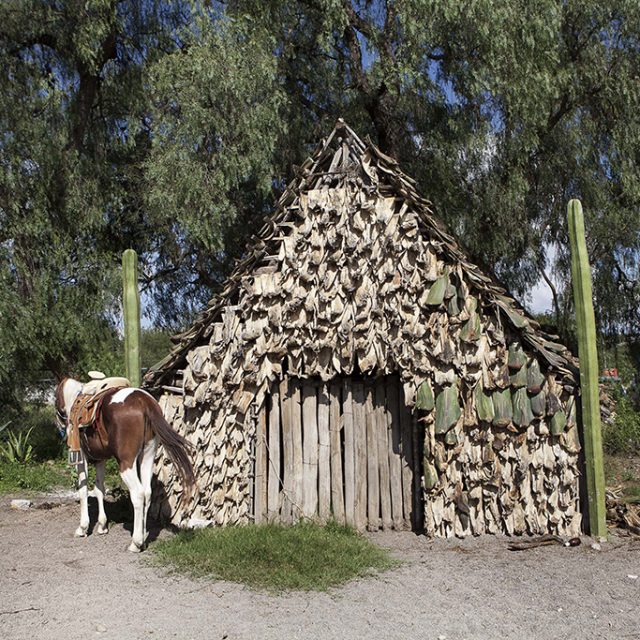

El paisaje luce gris en El Palmar, comunidad hnä hñü (otomí) de Santiago de Anaya. Cuando Venancia Cruz Dominguez describe la vida cotidiana aquí, una palabra es recurrente en su testimonio: tristeza

Los ñhathö resisten al despojo “legal” de su territorio

Publicaciones

Una autopista podría atravesar el Gran Bosque de Agua, en los límites del poniente del Distrito Federal con el Estado de México. Este bosque, uno de los últimos proveedores de agua y aire puro en la zona conurbada, será cortado por la autopista Toluca- Naucalpan, concesionada a la constructora Teya (filial de Grupo Higa) y promovida como “autopista verde”. El pasado 9 de julio, la presidencia de la República publicó un decreto de expropiación en el Diario Oficial de la Federación para abrir paso, “legalmente”, a las obras de construcción de la carretera.

None of Mexico’s missing 43 students are among 129 bodies found in mass graves

Publicaciones

Ten months since their disappearance, none of the students’ remains have been found in the 60 clandestine graves that have so far been uncovered around the city of Iguala, Guerrero.

Apatzingán: También fueron los militares

Publicaciones

APATZINGÁN, MICHOACÁN..- A las 2:30 am del 6 de enero, Día de Reyes, un convoy de la Policía Federal irrumpió por un costado del Palacio Municipal de Apatzingán. Momentos después, un destacamento militar lo secundó por el costado contrario. Ambos sumaban más de 100 fuerzas federales. En una operación de pinza, soldados y policías dispararon al plantón que una centena de elementos de la Fuerza Rural y simpatizantes, armados con palos, mantenían en los portales del Palacio.

Seis de los manifestantes portaban pistolas registradas pero se sujetaron a la orden de no disparar en caso de ataque, dada por su líder Nicolás Sierra, “El Gordo Coruco”. Algunos pidieron auxilio por su radio de comunicación y arribó una camioneta con guardias civiles provistos de palos.

Eugenio Argueta Flores era uno de los pasajeros. Él declaró ante la Procuraduría General de la República (PGR), integrada en la Causa Penal 3/2015-I en poder de la reportera, que: “al momento de identificarnos como autodefensas, la Policía Federal y la Militar nos dispararon con sus armas de cargo, nosotros caímos de nuestro vehículo y al momento de que nos dieron la orden de pararnos. me percaté de que un compañero de los que iba conmigo ya estaba muerto por causa de los disparos de la policía federal y de la militar”.

Segunda parte de investigación por Laura Castellanos (@lcastellanosmx)- Publicado en Aristegui Noticias. / Fotogalería

Las damas de la miel

Publicaciones

Esta es la historia de un insecto.

Es, también, la historia de una cultura.

Pero, sobre todo, es la historia de supervivencia del entorno que comparten abejas y mayas.

Empecemos contando lo que sucedió hace seis años en Cancabchén, una pequeña comunidad indígena del municipio de Hopelchén, en Campeche. De un día para otro, los hombres y mujeres que se dedican a la producción de miel se acongojaron al mirar miles de abejas muertas alrededor de sus apiarios. No conocían las causas. Ese año los habitantes del pueblo padecieron una fuerte crisis económica. En Cancabchén, poco más de la mitad de sus 500 habitantes vive de la producción de miel.

—Tenemos dinero por las abejas. Sembramos maíz, calabaza, pero eso es para nosotros, para el consumo de la familia, no para vender. Lo que vendemos es la miel. El sustento de la familia lo tenemos gracias a las abejas —quien habla es Angélica Ek, apicultora de 36 años y exrepresentante del comisariado ejidal de Cancabchén. Como la mayoría de sus vecinos, ella aprendió el manejo de la abeja Apis mellifera, al observar cómo lo hacían sus padres.

—Cuando un hombre cumple 18 años, su papá le da sus abejas. Es como su herencia, si él sabe cuidarlas, atenderlas y aprende a reproducirlas de ahí va a tener dinero.

– Las damas de la miel. Texto: Thelma Gómez Durán / Publicado en QUO número 205, noviembre de 2014

– Versión digital del impreso

Discrimination, disease and dignity

Publicaciones

Maurilia wasn’t strong enough to walk. When she spoke it was in a disjointed combination of Spanish and Tu’un Savi, one of the languages of the indigenous Mixtec people. She bit constantly at her fingers and seemed to have lost all sense of time and space.

But it wasn’t always like this. Maurilia had been born on November 12, 1982, and had studied until middle school. After that she had helped her mother and brother on the land.

Then, in 2002, at the age of 19, she began experiencing severe headaches and started to cough up blood. The hallucinations and loss of appetite came a little later. The following year, her health deteriorated further still. But with the nearest hospital at least a four-hour drive away, and no health services available within her community, Maurilia didn’t see a doctor.

Her village, Costilla del Cerro, is located between mountain ranges in the southern state of Guerrero. The region, known as ‘La Montaña’, is home to some of the poorest municipalities in all of Mexico and, according to a Human Development Index issued by the United Nations in 2009, the living conditions there are comparable to those in some sub-Saharan African nations. Most residents live off a harvest of beans, corn, chili and quelite, plants that are eaten for their leaves. Others emigrate to work in the fertile fields of the north or to try their luck in the US.

Maurilia’s mother tried all she could to help her daughter, even selling a plot of land in the hope of raising some money for medicine, while her brother, a migrant day labourer in the north of the country, made barely enough to survive.

But, with no money to pay for healthcare, Maurilia’s mental state deteriorated. She grew so aggressive that her family reluctantly began restraining her with a rope tied around her neck. Like this, she would spend her days walking around a tree or sitting on the floor. By night or when it rained, she would shelter beneath a loft made from branches.

That was how a team from the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center found her when they arrived in the village in 2008. I had come along with them and, although I’d been warned about Maurilia’s aggression, what I saw in her was sadness, thirst and exhaustion.

I tried to talk to her as a psychologist, lawyer and translator from our team spoke to her mother. I was reminded of the anger I’d felt as a child upon witnessing images of starving, disease-ridden Somali refugees in a photographic yearbook I’d been given as a gift. I never imagined I’d see something so similar in my own country, and I felt frozen with shock.

But Maurilia wasn’t the only resident of her village who displayed the disturbing symptoms of some undiagnosed illness. Agustín was 11 but had the body of a six-year-old. He was intolerant to sunlight and could only speak in individual syllables. His cousins displayed similar symptoms and his aunt said almost all of the children in the village had the same dark spots on their faces that had preceded the onset of illness in the others. Locals referred to it as mal de ojo or mal de luna, popular ways of explaining an unknown disease.

I questioned what I was doing there and wondered whether it wasn’t disrespectful to take pictures of people in such a plight. Could my camera help them in any way, or would it merely fuel some kind of morbid curiosity? I felt conflicted. But I had to make a decision quickly. So I picked up my camera and took the photographs.

But I wanted to preserve their honour and to show their strength. I wanted their stories to serve as an example of the consequences of Mexico’s public health policies and as an illustration of the depths of discrimination. Maurilia’s tale perfectly highlights that: as an impoverished indigenous woman with mental health problems she was among the country’s most vulnerable.

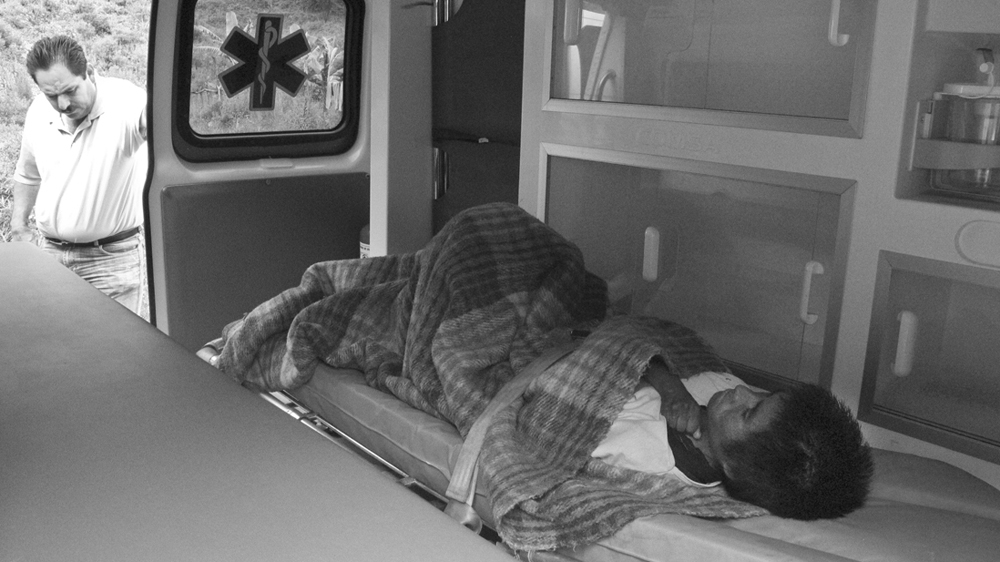

Alarmed by her condition, the human rights workers arranged for Maurilia to be transported to a hospital in the nearest city. When the ambulance arrived to collect her, the local children were so amazed by the sight of the vehicle that they ran out of their school to get a better look.

I do not know what happened to her after that – and even whether she is still alive. I tried to return to the village by myself two years later, but the person who had originally guided us there had been killed. And in this lawless part of the country where kidnappings are frequent, it was too dangerous to venture there alone. I’ve heard rumours that Maurilia has died and Agustín is no longer able to walk. But I cannot confirm these.

The images I took that day were first shown to the public in November 2011, as part of an exhibition by the Mexican office of Amnesty International, with the permission of the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center. Like the photographers Ricardo Ramirez Arriola, Karla Hernández and Enrique Carrasco, whose work was also featured, I wanted to make a statement about the strength and dignity of indigenous women. And there is no other context in which I would want these images to be seen.

Photogallery

As her mental state worsened and she grew uncontrollably aggressive, Maurilia’s family began tying her to a tree [Prometeo Lucero]

Costilla del Cerro is at least a four hour drive away from the nearest city and hospital [Prometeo Lucero]

A girl peeks into the kitchen of Maurilia’s home [Prometeo Lucero]

The shelter under which Maurilia sleeps [Prometeo Lucero]

Villagers watch as an ambulance comes to take Maurilia to hospital. For some, it was the first time they’d seen such a vehicle [Prometeo Lucero]

Maurilia’s mother watches as an ambulance arrives for her daughter [Prometeo Lucero]

Maurilia is placed on a stretcher in the ambulance [Prometeo Lucero]

Maurilia’s mother looks through the window of the ambulance [Prometeo Lucero]

Eleven-year-old Agustín suffers from stunted growth [Prometeo Lucero]

Children sit on a step. Agustín, left, and his cousin, on the right, are unable to walk or talk and are highly sensitive to sunlight [Prometeo Lucero]

A woman carries her son, who has markings on his face. She is concerned that he will develop the same symptoms as other children in the village [Prometeo Lucero]

Tlapa is home to the only hospital in the region. It is not unusual for women and children to sleep on the floor as they wait to be seen, and even though it is a public hospital, patients say they are often asked to pay [Prometeo Lucero]

La publicación digital de Al Jazeera Magazine publica la historia de Maurilia en la edición «What this picture means to me« (abril de 2015).

La publicación interactiva puede leerse a través de iPad [Descarga]

Actualización, 23 de octubre de 2015:

La historia puede consultarse ya directamente en el sitio web de Al Jazeera.

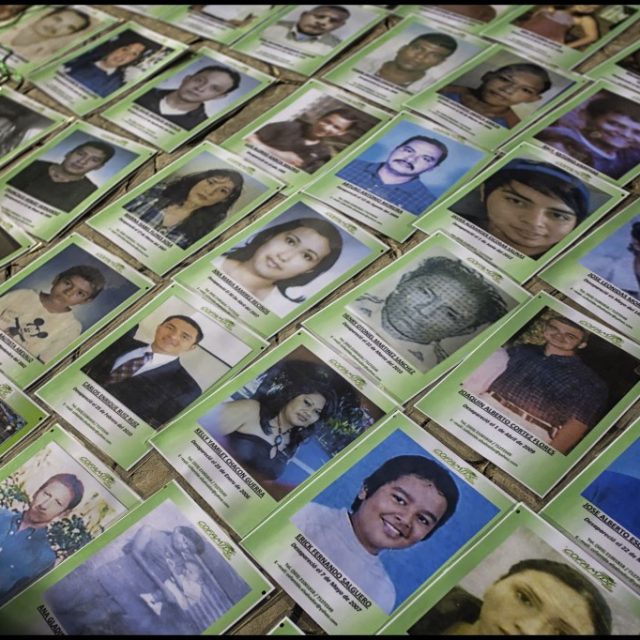

¡Uno, dos y tres, las madres otra vez!

Publicaciones

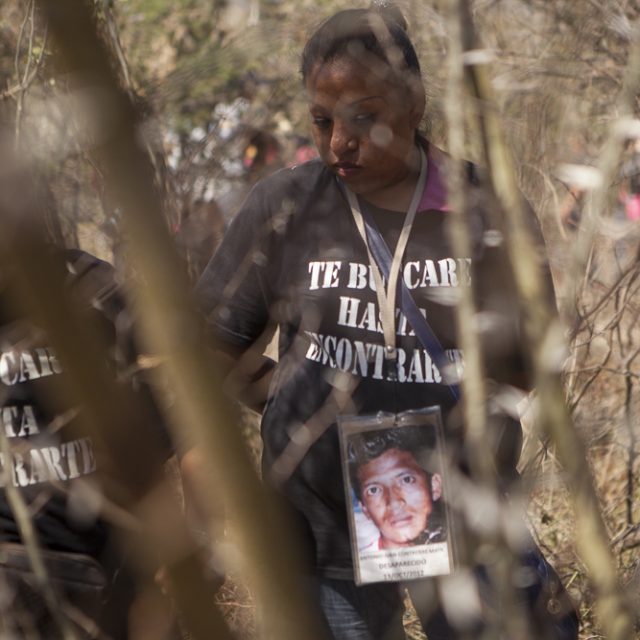

Un año más, madres de migrantes centroamericanos desaparecidos en el país recorrieron los mismos caminos que sus hijos para buscarlos.

De la semilla a la limonada

Publicaciones

Desde Tierra Caliente, Michoacán, hasta la Central de Abastos, Wal Mart o el tianguis, el limón desde su origen significa, además de un alimento, una fuerte derrama económica.

Este reportaje gráfico abunda sobre el costo del limón desde el pago a los trabajadores jornaleros en Apatzingán, Michoacán hasta el consumidor final en la Ciudad de México y su aumento en el costo.

Texto: Itxaro Arteta / Publicado en revista EXPANSION 1155, diciembre de 2014

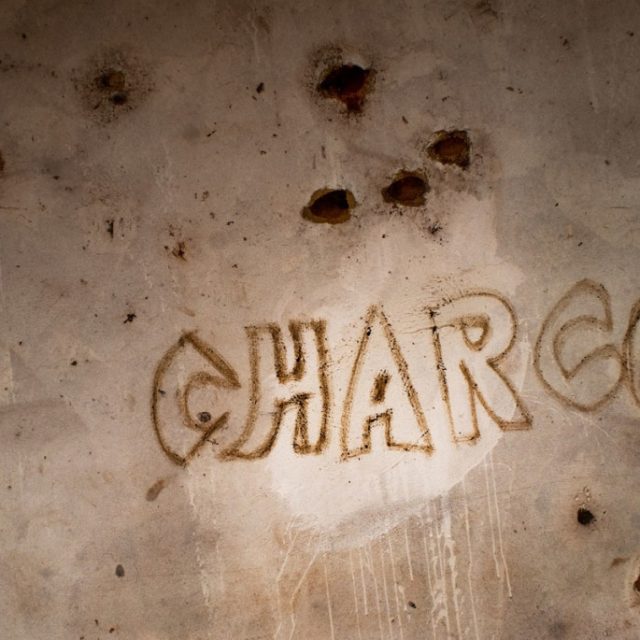

La masacre de El Charco, en Guerrero, antecedente de la tragedia de Iguala

Publicaciones

MÉXICO, D.F. (Proceso).- En junio de 1998, con Angel Aguirre Rivero como gobernador sustituto de Guerrero, ocurrió la matanza de El Charco: 11 jóvenes, supuestos guerrilleros, fueron ejecutados por soldados… como en Tlatlaya.

Proceso en su edición 1128, del 13 de junio de 1998, publicó un reportaje sobre la masacre de El Charco que, por su antecedente con lo ocurrido en Iguala y Tlatlaya, consideramos pertinente sea recordado.

A continuación, el texto íntegro, escrito por los reporteros Álvaro Delgado y Gloria Leticia Díaz:

AYUTLA DE LOS LIBRES, GRO. (Proceso).– Un grito que brotó de la oscuridad rompió la quietud de una madrugada salpicada por una leve llovizna:

—¡Salgan, perros muertos de hambre!

-> Proceso | La masacre de El Charco, en Guerrero, antecedente de la tragedia de Iguala

El pueblo cucapah se niega a su extinción en México

Publicaciones

EL MAYOR, BAJA CALIFORNIA.– En su lengua, Cucapá significa “gente del río” o “los que vienen y van donde va el río”. Durante más de 500 años, los integrantes de este pueblo amerindio han habitado las márgenes del delta del río Colorado, en el Valle de Mexicali, donde comienza la península mexicana de Baja California.

Son pescadores y artesanos. Los une la familia, la pesca, los kurikuri (rituales) y las ceremonias fúnebres. Y ahora, además, la lucha por no desaparecer, en una batalla que lideran sus mujeres.

“Soy Hilda Hurtado Valenzuela. Soy pescadora. Y soy Cucapá”, dice, a modo de presentación, la presidenta de laSociedad Cooperativa del Pueblo Indígena Cucapá, que también habita en el vecino estado estadounidense de Arizona.

-> Publicado en IPS Noticias | El pueblo Cucapá se niega a su extinción en México | Texto: Daniela Pastrana